Containers in High Performance Computing

What is Virtualization

Virtualization in general, is widely used to turn individual physical computer into several “virtual computers” that share same physical hardware. These virtual computers known as VMs (Virtual Machines) , realistically pretend to be independent computers on their own, each one booting and running an operating system of its own, as a physical computer would.

What is Containerization

Lightweight virtualization or containerization is the packaging together of software code with all it’s necessary components like libraries, frameworks, and other dependencies so that they are isolated in their own “container”.

The main reasons behind using containers for HPC are portability, composability and BYOE(Bring Your Own Environment) .

Containers vs Virtual Machines

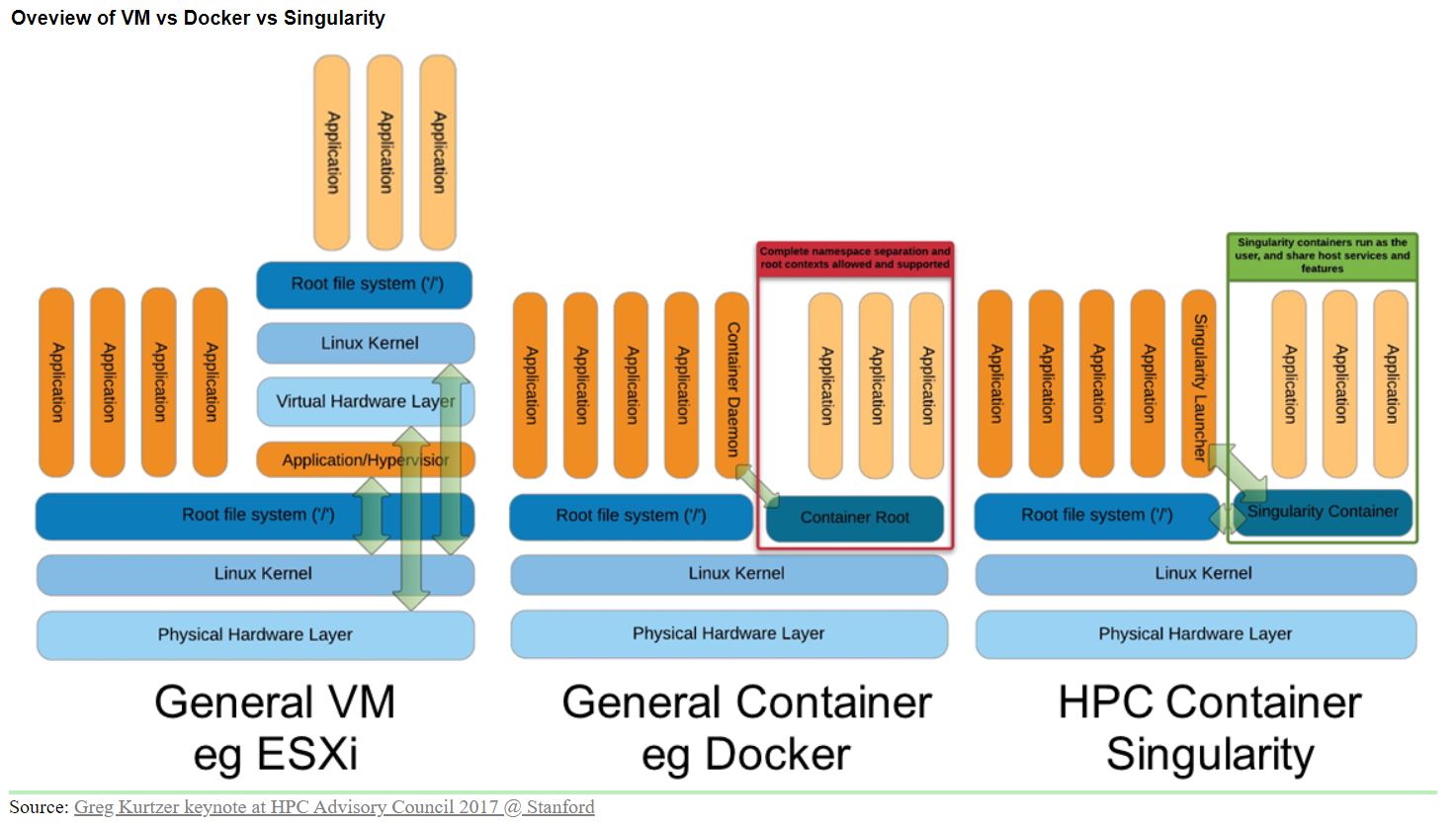

- Applications running inside a VM are not only further away from the physical hardware but the layers they must traverse are redundant

- Virtual Machines emulate a whole machine. In the case of containers, only the Operating System is virtualized.

- Additionally, there is a layer of emulation (Hypervisor) which contributes to a performance regression in VMs.

How does Containers matter for HPC

Containerization demonstrates its efficiency in application deployment in Cloud Computing. Containers can encapsulate complex programs with their dependencies in isolated environments making applications more portable, hence are being adopted in High Performance Computing (HPC) clusters.

General Workflow of Containerization

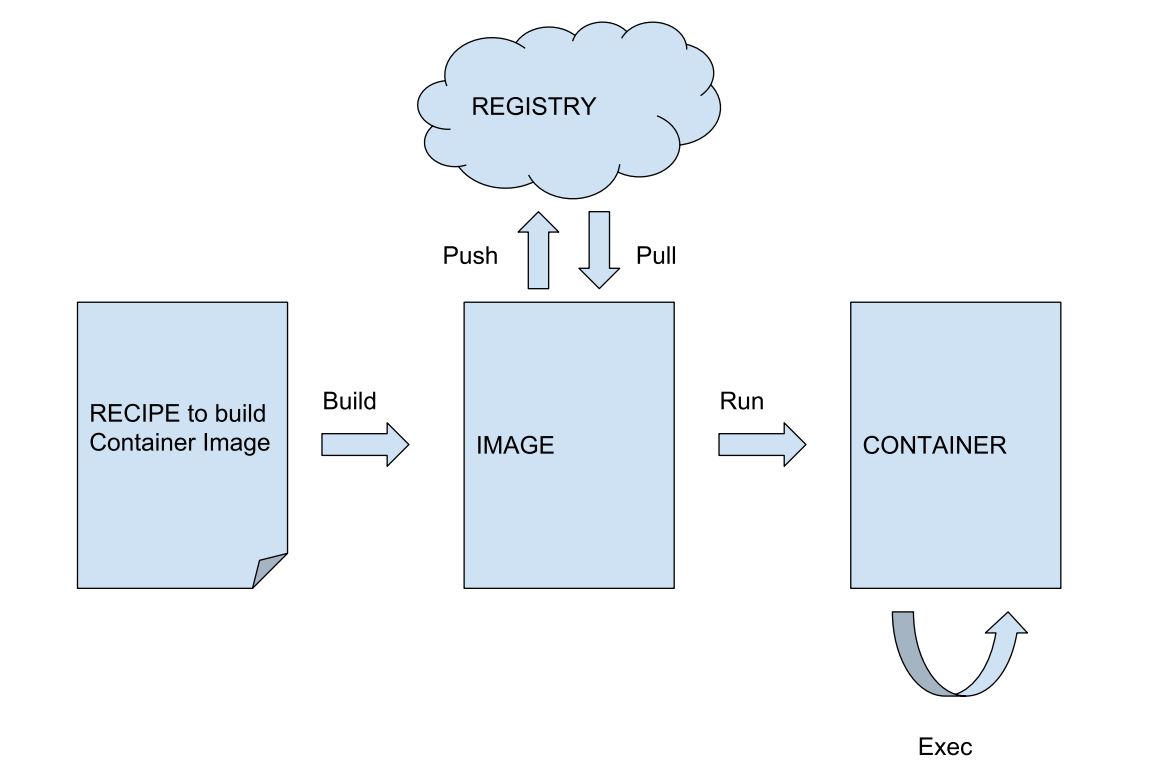

In a generic container workflow, a RECIPE file is used to build an IMAGE. These can be pushed-to or pulled-from a REGISTRY which could be local or also public in the cloud. By invoking the ‘run’ command on an IMAGE, a CONTAINER instance is started. Multiple CONTAINER instances of the same image can be started. The ‘exec’ command allows to execute any command of choice within a running container

Key Benefits of Containers

- Containers are “lightweight” and no need to set up a separate guest OS for each application since they all share the same OS kernel.

- Container images are stored as a single file which makes them easily shareable.

- A Container image can run on any system that has the same architecture (e.g., x86-64) and binary file format for which the image was made. This provides portability.

- A Container image bundles an application together with its software dependencies, data, scripts, documentation, license, and a minimal operating system. Software in this form ensures reproducible results.

- Containers virtualize system resources at the operating system level, providing developers with a view of the OS logically isolated from other applications.

- Containerization is a crucial tool for streamlining DevOps workflows. Users can create containers rapidly, deploy them to any environment, where they can be used to solve many diverse DevOps challenges.

Container features not wanted in HPC

- HPC applications cannot incur significant overhead from containers

- Micro-services container methodology does not apply to HPC workloads

- Containers allow root-level access control to users; On supercomputers this is unnecessary and a significant security risk for facilities

Basic Terminology

An image is a file (or set of files) that contains the application and all its dependencies, libraries, run-time systems, etc. required to run. You can copy images around, upload them, download them etc.

A container is an instantiation of an image. That is, it’s a process in execution that got spawned out of an image. You can run multiple containers from the same image, much like you might run the same application with different options or arguments.

In abstract, an image corresponds to a file, a container corresponds to a process. A registry is a server application where images are stored and can be accessed by users. It can be public (e.g. Docker Hub) or private.

To build an image we need a recipe. A recipe file is called a Definition File, or def file, in the Singularity jargon and a Dockerfile in the Docker world.

Container engines for HPC

Docker

- Docker is the industry-leading container engine, but Docker has several problems that affect its usage for HPC.

- Docker introduces several security concerns that are critical in an HPC environment, such as needing root permissions or being root inside the container.

- Docker uses TCP/IP for networking, and it is not trivial to make it use the custom interconnect of the HPC machine (for example, InfiniBand). Some developments have been made in order to solve these issues

Singularity

- The architecture of Singularity is such that common users can safely run their containers on a HPC cluster system without the possibility for root privilege escalation.

- Singularity, makes use of Linux kernel ‘namespace’ feature to isolate processes

- Singularity supports two image formats: Docker/OCI (Open Container Initiative) and Singularity’s native Single Image Format (SIF).

Shifter

- Shifter is a container engine developed by NERSC for HPC.

- Instead of a Docker/OCI format, it uses its own Shifter-specific format, but this is reverse-compatible with Docker container images. It requires hosting a registry service and a Shifter Image Gateway.

- The downside to Shifter is lack of community. There are not many other organizations other than NERSC and Cray that appear to support Shifter.

CharlieCloud

- Charliecloud is a promising container engine developed by LANL for HPC.

- Charliecloud supports both MPI and GPUs.

- One of the most appealing features is the active effort in moving towards a completely unprivileged mode of operation with containers. If Docker is available on the system, Charliecloud will use it as a privileged backend for pulling and building images.

- However, if no Docker is found (always the case in HPC), Charliecloud will fall back to its own unprivileged backends for pulling (experimental) and building.

Podman

- Podman is an open-source container engine maintained by Red Hat. It has quite similar features to Docker, with some important differences:

- Provides support for MPI applications and GPU applications.

- Runs daemon-less, making it simpler to deploy in a shared environment such as HPC

Interestingly, the API is mostly identical to that of Docker, so that in principle one could just use podman by means of

$ alias docker=podman

Enroot

- Enroot is Nvidia way of deploying containerized applications on their platforms.

- The tool has been kept simple by design and can run fully unprivileged. It comes with native support for GPUs and Mellanox Infiniband (unsurprisingly).

Creating containers for HPC workloads with Spack and Singularity

Spack is a package manager for HPC, with the main purpose of automating the build from source of scientific applications and their dependencies. It has many features and functionalities, with a relatively concise command interface to select compilers, package versions, dependencies, build options, and more.

Spack can also be used to automate the generation of Dockerfiles and Singularity def files. More information on how to customise the creation of Dockerfiles and def files with Spack can be found at the Spack docs on container images.

Installing Spack

Getting Spack is easy. You can clone it from the github repository using this command:

$ git clone -c feature.manyFiles=true https://github.com/spack/spack.git

This will create a directory called /spack. load Spack into environment by running below command

$ . spack/share/spack/setup-env.sh

Spack Environments (spack.yaml) are a great tool to create container images.

Step 1: Creating an Environment

$ spack env create myproject

Spack creates the file spack.yaml and the hidden directory .spack-env

Step 2: Activating an Environment

$ spack env activate -p myproject

Step 3: Add HPC application build specs to spack.yaml

$ spack cd -e myproject # will goto working location of env

$ vi spack.yaml

Consider having a Spack environment like the following, copy paste the below lines and save spack.yaml:

spack: specs: - gromacs+mpi - mpich container: # Select the format of the recipe e.g. docker, # singularity or anything else that is currently supported format: singularity # Sets the base images for the stages where Spack builds the # software or where the software gets installed after being built.. images: os: "centos:7" spack: develop # Additional system packages that are needed at runtime os_packages: final: - libgomp # Labels for the image labels: app: "gromacs" mpi: "mpich"

Step 4: Create Singularity definition

additionally the multi threading support is enable in the final container with the installation of the OpenMP runtime library libgomp. The definition file for singualrity can then be created with the command

$ spack containerize > gromacs-mpi.def

Installing Singularity

Singularity installation guide from official website: link

Build the container

With this definition the final application container image can now build with the command

$ singularity build --fakeroot gromacs-mpi.sif gromacs-mpi.def

where the --fakeroot switch to allow building for non root users. The build will have two phases, where the first one will pull in the container spack/centos7:latest which has spack and necessary build tools installed, build gromacs together with openmpi and move the resulting binaries to the container centos7:latest. The binairis built with spack are located in the container under /opt/view/bin.

Inspect the container

A single command within the container can be run with

$ singularity exec gromacs-mpi.sif ls /opt/view/bin

which will list all the binaries installed under /opt/view/bin within the container. You can also open a shell in the container with

$ singularity shell gromacs-mpi.sif

Please note that the home directory of the user is mounted under $HOME in the container.

Run the container

Now you can run the application, which is gromacs in this case, in parallel with

$ mpirun singularity exec gromacs-mpi.sif gmx_mpi mdrun\

-s topol_pme.tpr -maxh 0.50 -resethway\

-noconfout -nsteps 10000 -g gmx_sing.log